Pottery: Objects of daily life born from the flame

Until gas and electricity became commonplace, wood and charcoal were the main energy source for the fire used to forge iron, swords and farming tools and to make pottery, glass and many more of the objects of daily life. These days technology makes it easy to light a fire and control the temperature, but Kyoto being a place that holds strong to tradition, there are many people who chose to make things the old-fashioned way with a naked flame. Woodland Kyoto’s plentiful lumber and a tranquil environment make it the ideal location for artisans to immerse themselves in their work.

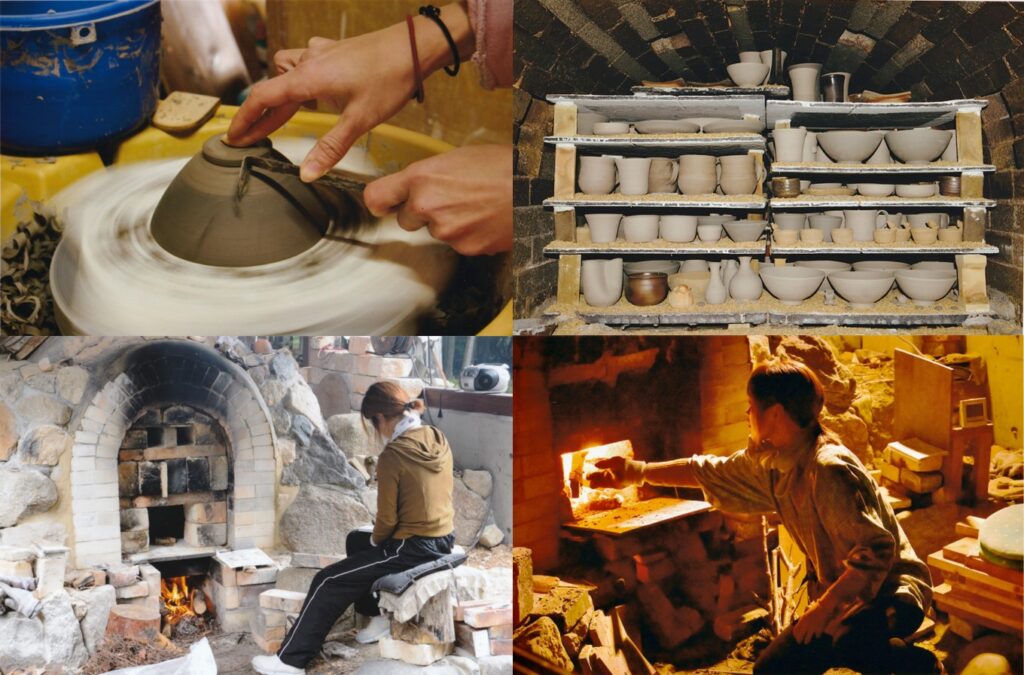

One such person is Emu Nakai, a pottery artisan born and raised at in the foothills of Hangokusan, a mountain on the western outskirts of Kameoka. Nakai works with a wood-fueled anagama (literally “cave kiln”) in a cypress forest near her childhood home. She built the kiln in 2010, clearing the space in the forest and stacking the bricks herself.

According to Nakai, anagama have been used for more than 1300 years and are the oldest type of kiln in Japan. She says that enclosed kilns were a significant technical innovation over the open burning that had been practiced until then, and the principles of firing and structure of the kiln have remained largely unchanged since.

Nakai fires up the kiln about three or four times a year to bake various items, typically tableware, vases, and pieces of artwork. It takes three days to heat it fully with family members taking turns around the clock to stoke the fire. The first day is spent burning out moisture from the base. On the second day, the temperature is gradually increased, and it reaches about 1200 to 1300 degrees Celsius inside the kiln on the third day.

Nakai fell in love with and trained in yakishime, a traditional technique of making unglazed pottery in a wood kiln that exploits the natural qualities of the clay. Because of the constant fluctuation in the state and flow of the fire in this type of kiln, there’s an unpredictability that gives the finished pieces a range of decorative expressions. For instance, small stones in the clay might burst and create a pattern on the object, or an object might be blackened by a shower of ash. Yakishime pieces also have a shiny, colorful “natural glaze” that is the result of ash melting at high temperature and fusing with the clay.

“There are people who say that electric or gas kilns are more convenient, but I’ve disliked working with machines ever since I was a kid. It’s far more convenient to control the flame directly with my own two hands and it suits my nature,” says Nakai. “The moment I extract the pieces from the kiln is the happiest of all. I’m excited when I get a color I was aiming for and it’s fun when a chemical reaction in the kiln has created something new too!”

Some of Nakai’s work. In contrast to conventional yakishime pieces which are typically rustic and heavy, Nakai’s are finer and more dainty-looking. They feel surprisingly light to hold and her expert potting and shaving skills are apparent in every detail. The techniques Nakai uses to create this finer pottery were actually developed by Kyoto ceramic artists. They aren’t popular in yakishime because the finished product tends to be too fragile, but Nakai continues to forge her own unique approach, hoping to make this style of pottery she loves more readily enjoyable for others.

“The beauty of yakishime items is that the more you use them, the more the gloss and color develop, and the more the feel improves. Because the clay is porous, you get a great layer of foam on beer and water tastes smoother. In a yakishime flower vase, the water will last longer too,” says Nakai. The deeper one goes, the more there is to these beautiful pieces.

Kikyogama (Emu Nakai’s kiln)

https://www.instagram.com/kikyo_gama/

Nakai’s work is available for purchase from time to time at exhibitions.