Visitors who know of the area might think first of the famous Rurikei (a name shared by a forested natural park, a gorge, and an onsen), but apparently, there’s more to the area than that.

I’d heard that Sonobe in Nantan City is a town full of mysteries and romance, with attractions that rank amongst “Japan’s oldest” or “Japan’s only,” so I set out from JR Sonobe Station to see it for myself.

Right away, I boarded a bus from the station bound for Kameoka.

The buses come about once every hour, so it seems you need to be careful so you don’t get stuck waiting at the start of your journey.

After a three minute ride rocking slightly on the bus, I got off at Sakaemachi bus stop. Walking for about ten minutes through the peaceful countryside, I arrived at my destination, the first of this trip: Ikimi Tenmangu Shrine.

Inspiration

Racing Through Time in Nantan: In Search of the Forest’s Hidden Treasures

2025.11.14

A Journey to the Town of Sonobe, to Find What Can Only Be Found Here

One Shrine, Five Stories. Receiving blessings at Ikimi Tenmangu, Japan’s oldest Tenmangu Shrine.

Of the 12,000 Tenmangu Shrines said to be found across all of Japan, this is said to be the oldest, and the only one to enshrine the 9th century scholar, poet, and politician Sugawara no Michizane (enshrined at all “Tenmangu” shrines) while he was alive.

Looking up from the road, I can just make out the shrine buildings atop a stone wall, laid as if for a mountain castle.

A plum tree in full bloom greets me on to the torii gate’s right – it already feels like a good omen.

Stepping into the grounds, I’m welcomed with warm smiles by Chief Priest Masahide Takebe and his wife, Yukiko Takebe, the assistant priestess.

Chief Priest Masahide: “Welcome to our shrine. I am Masahide Takebe, the 38th generation chief priest.”

Interviewer: “I heard that Sugawara no Michizane was still alive at the time this shrine was built. Is that true?”

Chief Priest Masahide: “Yes, the history of this shrine goes back to the year 956. Its founder, Takebe Genzo, had ties to Michizane, who had a residence here in Sonobe at the time. When Michizane was exiled to Dazaifu, Genzo was secretly entrusted with the care of Michizane’s children, which marked the beginning of this shrine.

To pray for Michizane’s safe return, Genzo himself carved a wooden statue in his likeness, built a small shrine to house it, and began praying to it as a living shrine (iki hokora). That was the first of the Tenmangu shrines.”

Interviewer: “And you’re a direct descendant of the same Takebe Genzo.”

Chief Priest Masahide: “Interestingly, Takebe Genzo also appears as a character in Japan’s three great kabuki plays. Because of that connection, many kabuki actors have come here to pray over the years.”

Interviewer: “I can hardly keep up with the scale of this story!” (laughs)

Assistant Priestess Yukiko: “Ikimi Tenmangu’s main hall enshrines Sugawara no Michizane, but we also have a shrine dedicated to Takebe Genzo. There are a total of 15 shrines within the grounds, each of them with their own story.

For example, at the Daijingu Shrine here, both the Inner and Outer Shrines of Ise Jingu* are enshrined. When you pray here, you’re facing in the direction of Ise Jingu, so it counts as if you had made pilgrimage to the shrine at Ise. It’s a kind of remote worship site.”

*Ise Jingu Shrine is an important shrine in Mie Prefecture dedicated to Amaterasu, the Shinto goddess of the sun.

Interviewer: “So a visit here even includes a visit to Ise Jingu Shrine!”

Assistant Priestess Yukiko: “Then there’s Akiba Atago Shrine, where legend says a raging fire once came to a stop and extinguished itself in front of the building.

“And Itsukushima Shrine, which you passed on the way up to the main shrine. The Itsukushima Shrines on Hiroshima’s Miyajima Island and Shiga’s Chikubu Islands are much more well-known, but our shrine’s Itsukushima Shrine has actually been a site of worship here even before Ikimi Tenmangu Shrine was established. It served as the guardian deity of this land.

“It’s surrounded by a small moat, and when priests from Hiroshima’s Itsukushima Shrine visited, they were impressed at how faithfully it has been maintained.”

Interviewer: “In that case, since I’ve come this far, I’d better visit all of the shrines here and offer prayers at each before I go.”

Ikimi Tenmangu Shrine

Address: 67-1 Misonocho, Sonobe-cho, Nantan-shi, Kyoto Prefecture

Telephone: 0771-62-0535

Access: 11 minutes on foot from “Sakaemachi” bus stop

Website: https://www.ikimi.jp/en/

Ikimi Tenmangu Shrine

Dedicated to Sugawara Michizane, famous as a deity of learning, Ikimi Tenmangu Shrine is the oldest of the Tenmangu shrines in Japan, built during Sugawara Michizane’s lifetime. This shrine is said to …

A delicious bite at an old eatery…Beloved by 19th century statesman and samurai, Kogoro Katsura?

After praying and receiving blessings at the shrine, I return to the pastoral scenery of the rice fields and walk for fifteen minutes.

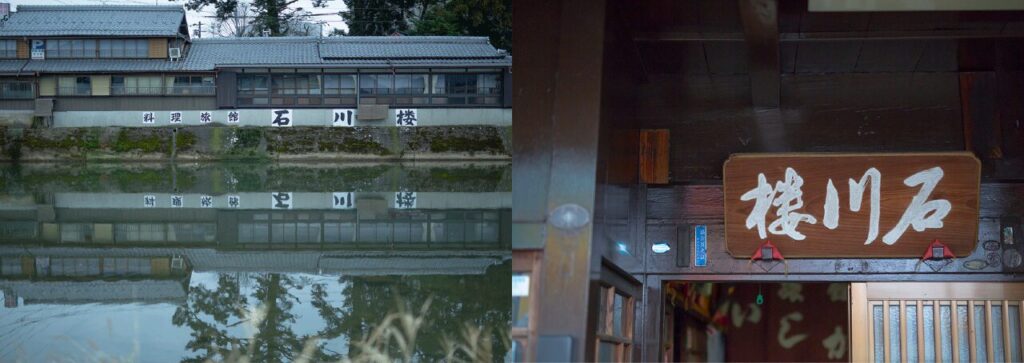

Just as I was starting to feel hungry, I arrive at Ishikawarou, a long-established restaurant that’s been around since the Edo period (1603-1865). The building juts out over the river like a kawadoko (river terrace), and a wonderfully simple, handmade sign out front catches my eye: “It’s thought that Kogoro Katsura once hid nearby.” It seems like we’ve stepped out of the ordinary.

The signboard beside it explains that during the Edo period, the restaurant was called “Rakushitei,” and was frequented by samurai and ladies enjoyed catching fireflies and playing in the river.

My curiosity fully piqued, I step inside.

The moment I enter, I’m struck by how spotless and neatly arranged the interior is. This restaurant has been around for over 150 years, but it doesn’t feel dated at all. From the tables and flooring – even the beer in the fridge has been perfectly arranged! It’s the kind of meticulous order and care that’s a testament to a shop that’s been running as long as this one has. As I’m admiring it, the owner and his wife appear, all smiles.

Ishikawarou Owner: “Welcome! Thank you for coming all this way to such an old restaurant!”

Interviewer: “Your restaurant has been running since the Edo period, for over 150 years. Which generation of owners are you?”

Ishikawarou Owner: “I’m the fifth generation. My brother was the fourth, and at that time I was training at a ryotei* restaurant in Kyoto, so it was after that that I came back to take over the business.”

*Ryotei are typically traditional fine dining restaurants.

Interviewer: “Is there someone who will carry on the business after you?”

Ishikawarou Owner: “My son is a chef, and he says he’ll step in to take it over, but I wonder if that’s really the best idea.”

Interviewer: “It’s not often you find a restaurant as lovely as this. I hope your son does carry on the tradition!”

Since we were chatting, I went ahead and asked about the sign, which I hadn’t been able to get out of my mind.

Interviewer: “Just outside the restaurant, there’s a handmade sign that says Kogoro Katsura once hid here – is that true?”

Ishikawarou Owner: “I don’t know if it’s true for sure, but it must be. After the Hamaguri Gate Incident at the end of the Edo period, he apparently disguised himself and went into hiding here. But since we can’t officially confirm it, we have to write ‘it’s thought’, you see.” (laughs)

Interviewer: “It did say, ‘it’s thought,’ that’s true. Thinking that a historical figure like Kogoro Katsura was once here, looking out at the same scenery kind of gives you chills, doesn’t it?”

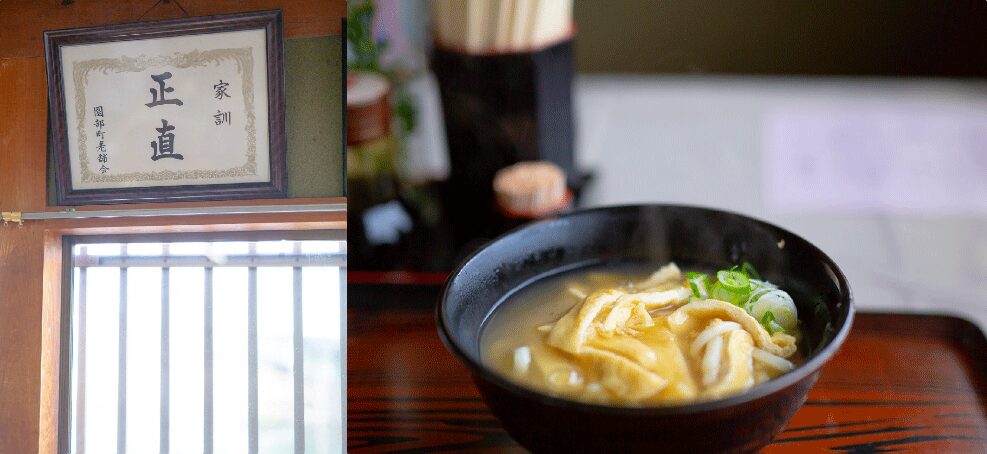

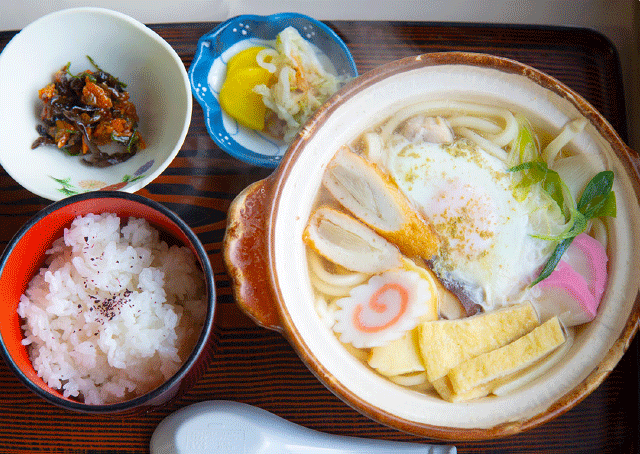

Chatting with the owner, my stomach’s beginning to growl, so I order some hotpot udon noodles (nabeyaki udon), tanuki soba noodles with fried tempura bits, and ankake udon noodles with their thick, starchy sauce.

The broth in these dishes is gentle and exquisite – as you might expect from training at a Kyoto ryotei restaurant. The noodles are not the firm kind that we’ve all grown accustomed to, and are much closer to the old-fashioned style of Osaka udon. As I eat, locals continue to enter the restaurant, and I overhear them chatting easily with the owners in the local dialect:

“Let’s all order the same thing so it’s not too much trouble.”

The owner’s wife laughs and assures them, “Oh, goodness, you don’t have to worry about that.”

It’s heart-warming to listen to their banter.

Spirits lifted, it’s time for me to head to my next destination.

Ishikawarou

Address: 16 Uehonmachi, Sonobe-cho, Nantan-shi, Kyoto Prefecture

Telephone: 0771-62-0245

Website: http://www.cans.zaq.ne.jp/ishikawarou/

A look into the only velvet factory in Asia!

A few minutes’ walk from Ishikawarou, , a large factory suddenly appears, covered in brown corrugated iron. The sign standing out front reads “Japan Velvet Manufacturing Co., Ltd.” (Nihon Birodo Kogyo Kabushiki Gaisha), and I’m immediately struck that the whole building looks like a movie set. Frankly, it looks incredibly cool.

Peering into the dimly lit interior, I can make out an array of enormous looms of a type I’ve never seen before. It puts me in mind of industrial heritage sites like the Tomioka Silk Mill, Japan’s oldest. I was even more surprised knowing that these looms are still in use today.

Just as I’m bracing myself to meet some stern and intimidating craftsman, out comes the cheerily smiling Akihito Fujimoto, the 5th generation owner.

Right away, he takes me on a tour of the factory.

Mr. Fujimoto: “This factory was built in 1922. It’s the only remaining velvet factory in Japan, and now the only one left in Asia.

“Tengaju, as velvet is known in Japanese, means “a fabric as soft as swan feathers,” and it was said to have been introduced to Japan about 450 years ago through trade with the Portuguese. Famous historical figures like warlords Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu wore velvet military coats and cloaks as symbols of their wealth and power.”

Interviewer: “So those red cloaks worn by 15th century samurai were velvet!”

Mr. Fujimoto: “Later, during the Meiji Period (1865-1912), velvet became a highly valued material for straps on footwear, and for a while it was very popular. At its peak, this factory employed over 120 craftsmen. Eventually, cheaper synthetic fabrics overtook velvet, though and today there are three velvet craftsmen working in Japan, and just fifteen in the world, it’s thought.”

Interviewer: “Just fifteen in the entire world? So this is an incredibly rare and specialized craft.

“I have to ask, by the way, are velvet, velour, and velveteen all the same thing? It still seems pretty common to encounter velour.”

Mr. Fujimoto: “They’re made from different materials and with different methods: for example, velvet can be made with rayon, but traditionally it’s made from silk. Of course, the characteristics of the nap and the feel of the fabric will be very different, too.

“In the case of velvet, everything is handwoven, so it takes about a week to weave 6 meters of fabric. Velveteen and other fabrics were developed later as machine-made, more efficient alternatives. But honestly, even we find it hard to explain the difference – it’s like trying to define the difference between biscuits and cookies.”

Interviewer: “I guess without ever touching real velvet it’s hard to understand the difference, too. Since this is the only place in Japan that produces real velvet, your machines must be one of a kind, too. How do you handle maintenance or repairs?”

Mr. Fujimoto: “There are no replacements, so if something breaks I have to fix it myself. When we run out of parts, I make them.

“Actually, last year, our old Taisho era (1912-1926) factory was struck by lightning and burned down. Even then, I made a mad dash to salvage any parts I could from the ashes before anything else. A lot of finished velvet burned too, but as long as we still have the tools we can keep making it.”

Interviewer: “As long as you have the tools, you can continue on… That’s true craftsmanship, what dedication.”

Even though production has declined, velvet from this factory is still used in important cultural properties like the yamahoko floats for Kyoto’s traditional festival processions. As Mr. Fujimoto told me, “If we want to keep preserving them with the craft’s authentic, traditional techniques, we can’t let this flame go out.”

Each loom has a label bearing what looks like a name. When I ask Mr. Fujimoto about them, he tells me he’s named them all after battleships, just for fun.

It’s a glimpse, I think, of his deep affection for the art of velvet weaving.

Japan Velvet Industries Co., Ltd. (Nihon Birodo Kogyo Kabushiki Gaisha)

Address: 125 Wakamatsu-cho, Sonobe-cho, Nantan-shi, Kyoto Prefecture

Telephone: 0771-62-0128

Advance reservation is required for factory tours (Open weekdays only until evening, closed weekends)

Website: http://www.cans.zaq.ne.jp/velvet/

Filling up on all of Sonobe’s natural blessings with glamping

From Japan Velvet Industries, I take the bus back to Sonobe Station.

For the last stop on my trip, I’m going to get my fill of nature – and food! – in Sonobe with a little “glamping” experience. From here, I hop on the shuttle bus and am whisked away to GRAX, a glamping site within Rurikei Onsen.

A 30 minute drive through the Rurikei area’s beautiful scenery, and before I know it, I’ve arrived. The wooden reception area is spotless and bright, more like a highland resort than a campsite. While new glamping facilities seem to be popping up everywhere lately, I’ve heard that this place has several unique touches you won’t find elsewhere.

My guide is Manager Koji Nishioka, a delightfully pleasant young man who seems to fit right in with Sonobe’s natural surroundings.

Interviewer: “This is my first time glamping, so I appreciate you showing me the ropes! How should I start?”

Mr. Nishioka: “We prepare all of the food ingredients and fire starters, so all our guests have to do is enjoy the cooking and eating. At GRAX, we use a lot of local and Kyoto-grown ingredients, and every recipe is easy to follow. Let me show you your tent.”

He leads me to the most stylish-looking tent I’ve ever seen. A large tarp has been set up in front of the tent, which seems to be for cooking and dining. I’m instantly excited when I see the large barbecue grill and the Dutch oven.

Inside the tent there’s a bed and a refrigerator, and even a heated kotatsu table, transforming this mountain site into my own little home.

Seeing all this convinces me that what I’ve heard is true: glamping is for everyone, no matter your age or gender.

Mr. Nishioka: “At night you can sometimes see deer wandering around the area, and since we’re at an elevation of 550 meters, there’s also wonderful stargazing.

“The rice is all grown locally in Sonobe, and from spring to autumn we run a ‘vegetable market’ where you can pick your favorite Kyoto vegetables for your barbecue. The thing that makes GRAX really special is that you can enjoy not just glamping, but also hot springs here.”

Interviewer: “It’s wonderful to be able to enjoy local food, but hot springs, too? That’s really something!”

Mr. Nishioka: “There are walking courses nearby through Rurikei Gorge, so you can do a little hiking, see the waterfall, and enjoy nature, too.”

Interviewer: “So you’ve got glamping, hot springs, and hiking. It sounds like all the best of Sonobe.”

Following the recipe, my food came out beautifully, and I eat my fill. At night, the entire campsite is lit up, and offers a different feeling than it did during the day. In all of the tents, everyone was enjoying their own special glamping moments.

On my way home, I find plenty of souvenirs like salad dressings and wines made with local Nantan ingredients – perfect mementos for your trip. As the night closes in, I return to the shuttle bus for the journey home.

I can’t help but feel that the Nantan area of Kyoto Prefecture still has much more to discover.

I wonder what kind of adventure I’ll plan here next?

GRAX PREMIUM CAMP RESORT

Kyoto Rurikei

Address: 1-14 Hirodani, Oigawa, Sonobe-cho, Nantan-shi, Kyoto Prefecture

Telephone: 0771-65-5001

Website: https://www.grax.jp/

GRAX Premium Camp Resort, Kyoto Rurikei

This is a new style of camp that you can enjoy comfortably empty-handed. There are nine types of camping sites available, including glamping tents, mobile homes, and cabins, etc. Here, you can play in …